At a candle-lit dinner alongside the Zambezi River, I dine with a table full of wildlife enthusiasts. I am among expert photographers and seasoned world travelers who have chosen Zambia for their safari, some on their fourth trip just to the Lower Zambezi. One woman pleads with me, “Don’t tell people about Zambia! Let us keep it for ourselves,” and I understand her concern. While the country should already be recognized as a top-quality safari destination, it is considered by many an esoteric adventure for well-traveled wildlife enthusiasts, or not considered at all. Documentaries allude to legendary national parks, such as the South Luangwa, but lacking adequate tourism budget, Zambia’s treasured safari parks have yet to step out of the shadows from the eclipsing notoriety of the Okavango Delta, Kruger, Masai Mara, and Serengeti. With a small number of intimate camps inside the park boundaries and a myriad of activities from off-road game drives, night drives, guided walking safaris, boating, fishing, and canoeing, there is a greater level of freedom and fewer crowds than the national park experience of other countries. This treasured balance is what creates such a high return traveler rate and their possessive lust for its unspoiled experiences.

LOWER ZAMBEZI NATIONAL PARK

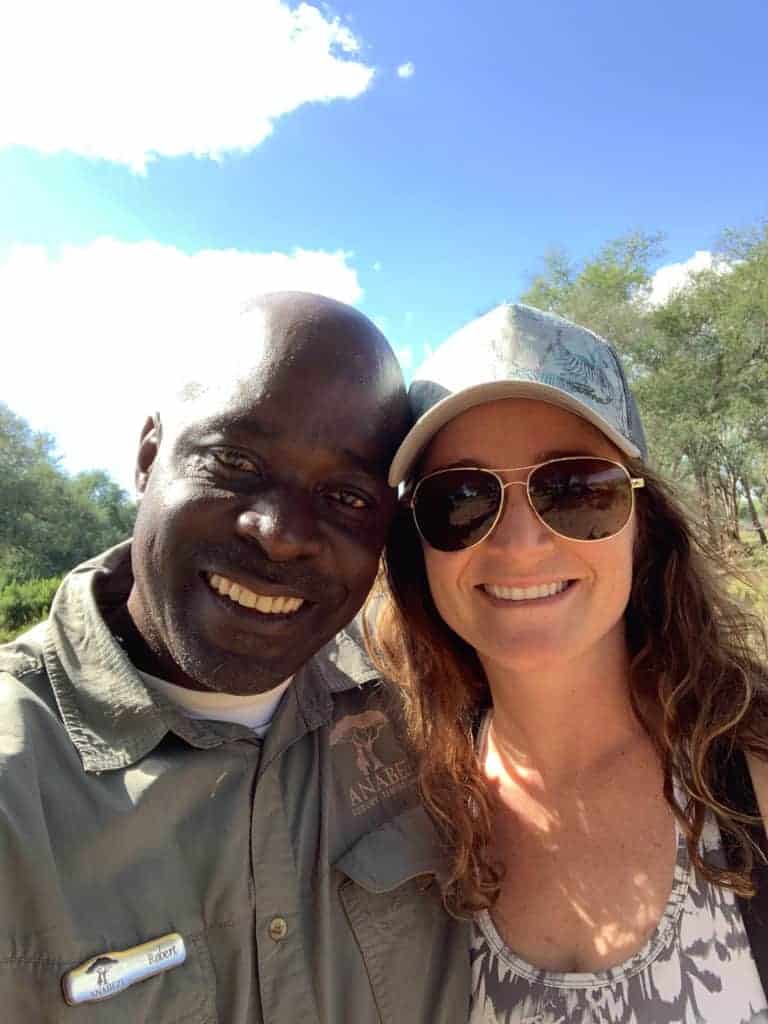

Having already visited Zambia’s most well-known park aside from Victoria Falls, the South Luangwa, my trip dives into two parks that are new to me: Lower Zambezi and Liuwa Plains. My journey begins in the Lower Zambezi National Park where I plan to experience each of the camps inside the park to understand their unique strengths. After a scenic flight over the Zambezi River where we can see elephants grazing and pods of hippos, I am met at the Jeki Airstrip by my private guide, Robert, a veteran guide of 23 years in Zimbabwe and Zambia. Robert asks about my interests, but it becomes clear what my goals are as I am distracted during his orientation by the background landscape of waterbuck, elephant, zebra, baboon, ground hornbill, and impala. So, we set out on safari, stopping for a black-chested snake eagle attempting a kill and white-backed and hooded vultures soaring overhead. I hear the raspy coughs of male impalas staking their claim for breeding rights, a near endless display of territorial might that persists both day and night this time of year.

The damming of Lake Kariba in the ’50s, the world’s largest man-made lake by volume, reduced the size of the Lower Zambezi River dramatically. In the old riverbed, we find herds of elephants and buffalo grazing under a canopy of winter thorn acacias, otherwise known as Anas trees. A pioneer species, the winter thorn favors the sandy riverbeds that lack nutrients for other trees to germinate but return nitrogen to the soil to allow secondary species to root. The elephants, with their tiny calves, warn us to keep a distance as they seek shade and graze beneath the acacias while four Southern ground hornbills graze nearby. As we reach the Chakwenga Plains, I spot a shadow in the distance and ask Robert to stop the car. “Lion,” I say after confirming with my binoculars, and he excitedly gives me a high five. He saw them before picking me up from the airstrip but, nonetheless, was genuinely thrilled to congratulate my spotting. Later, Robert notices a fresh drag mark along the road where a leopard has relocated its kill, and he plans for the afternoon. After two productive hours, we arrive at camp for a late lunch where I meet the Anabezi staff led by Solomon, or Solly, who like Robert was an original guide with Wilderness Safaris decades ago and has managed camps in Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana.

ANABEZI + AMANZI CAMPS

Anabezi and Amanzi Camps are sister camps about ten minutes’ drive from one another. The camps are the farthest east in the park with dense mopane woodland to the east that creates a natural buffer zone far from villages, and to the west is Old Mondoro, about thirty minutes’ drive from Anabezi. With tents that are approximately 1000 sq. ft. and generous private decks, the rooms are elegant and very comfortable boasting an indoor bathtub as well as an outdoor shower that overlooks an acacia woodland and waterway that flows into the Zambezi River. Zimbabwe’s Sapi Reserve east of Mana Pools National Park lies in the distance across the river. The rooms are connected by a tall boardwalk to the main lodge where the massive deck provides excellent viewing of elephants grazing and birdlife.

In the afternoon, we stop for a history lesson at the Kenneth Kaunda Ruins, named for Zambia’s first president who used the buildings as a vacation spot before the park was gazetted. We find Lillian’s lovebirds, sacred and hadeda ibis, Swainson’s spurfowl, white-browed coucal, and relocated the two lions we had left earlier. Blackie, the older male, is limping and getting harassed by the flies. He is among a coalition of three; the two others are brothers that joined forces with him over the last year. Blondie has a fresh gash below his eye and a short, thin mane.

We continue through thickets and dry riverbed where, turning the corner, we are surprised by the Anabezi team waiting for us with sundowners. Candles line the sand, and director’s chairs circle a bonfire and well-stocked bar. We enjoy delicious canapes and gin and tonic before setting out again for a night drive. Anabezi’s guides manage both the driving and the spotting with white torchlight converted to red light filters when predators are spotted. Not ten minutes after departing from sundowners, Robert spots a male leopard near the road where he saw the drag mark earlier in the day. To our surprise, one leopard becomes two—a male and female sibling pair! They stay for a bit and then set off into the dense underbrush. Before reaching the camp, Robert also spots a civet, then later a genet.

The next day, we set out on a morning game drive. I have the choice of walking, driving, or boating any time of day, but I want to see more of the available wildlife in my short stay, and the vehicle is the fastest way to that goal. Robert pauses the vehicle to identify hyena tracks on the road and explains how the front foot is larger than the back with a duck-footed angle to the print. Robert heard lions calling early in the morning, so we set out to see if the coalition was reunited, passing through Jesse bushes preferred by leopards, and stopping to admire a drop tail ant colony before arriving at the lions, still sleeping in the Chakwenga Plains.

Robert hears a baboon alarm call from the forest towards the river, so we set out to investigate. Following the signals from alert impala, we are graced by the presence of two leopards on the move. They slink into the riverfront tallgrass, and Robert repositions the vehicle further downstream with the hope that they will resurface. The female re-appears first, making a quiet, raspy call that Robert explains is possibly to her cubs. From behind her, a young male leopard appears and turns back into the tall grass. And, to our astonishment, a young female leopard slinks down the riverbank and onwards west; three leopards, not two!

Delighted by our luck, we return to the lions, who moved closer to the baboon commotion hoping they could steal a kill but opt instead to relax in the shade. Robert selects a scenic oxbow lagoon for our coffee break where herons line the riverbank, bee eaters circle the acacia trees, and an African fish eagle calls nearby. We return to the lions to find the third male has joined them and then continue to the drag mark where a beautiful male leopard casually relaxes in the shade will a full belly.

We return for a lunch of tender steak, salad, potatoes au gratin, and quiche, and it’s no surprise that the camp earned the 2019 Safari Award for Best Cuisine in Zambia. The tranquil scene of an elephant grazing in the winter thorn acacias complemented the meal nicely. After the mid-day siesta, we head out on the Zambezi river to try our luck at catching a tigerfish. We wind through the Zambezi on a motorboat passing elephants, crocodiles, hippos, and cape buffalo to reach the Ngwenya Channel where the tigerfish enjoy lurking in the junction to prey on small fish that seek the safety of the channel. My fishing guide, Justin, sets me up with a chunk of fish for bait and I cast. These clever fish are a challenge not only because of their power but often bait will come back nibbled entirely around the hook. Justin’s line, however, gets a big pull so he sets and hands me the rod to feel the fight as I reel it in. We keep it long enough to measure and take a picture before returning to the shallow waters to revive in safety.

After sundowner cocktails and snacks, we return to the camp and immediately set out on a night drive. The drive is abbreviated to fit in fishing, but we still encounter three more leopards within a half an hour, our tally increasing to nine sightings. Two of the leopards, an adult male, and adolescent female are together relaxing in the sand of a dry riverbed. Farther away in the acacia woodland, we find an adult female on the move. On the way back, we spot two more civets, as well as several genets, which I am discovering, are as anticipated as nightjars here.

The next morning, we set out again on a game drive, stopping to observe some of the plants and birds with no intended focus on mammals. However, while driving through thickets of croton bushes, we encounter an adult female leopard (different adult from the one we found the night before) and her two cubs, one of which is the young female from the night before who was seen presumably with her father. One of the goals of Anabezi Camp is to catalog the big cats, and they have contracted with a freelance guide, Taylor, to collect the data that the guides can then build off and share with Conservation Lower Zambezi. Like our model in Tanzania from Njozi Camp, this will greatly enhance the guests’ safari as they keep track of individual cats and learn how they relate to the ecosystem.

We pause to admire a scarlet chested sunbird and Namaqua dove, then return to the lions, still relaxing in the shade in the same spot as the day before, but this time with full bellies. We continue in search of the third male and find him with a lioness and two timid cubs no more than a few months old. We set out to the Chakwenga Plains to photograph a beautiful fallen Ana tree framing a termite mound that I had admired the day before, this time accompanied by a pair of mating impalas. On our way back to the lions, Robert notes a new drag mark from a leopard kill. We search for the leopard but instead spot the front leg of an impala stripped clean. Robert predicts that the full bellies of the lions indicate that the leopard’s kill was stolen. We explore the dry wash on foot where we locate more cleaned bones, the spot where the intestines were discarded, leaving only a stained spot of dark, wet grass after the nocturnal predators had their turns on the leftovers. Footprints indicate that the lions had been there as well as the leopard; Robert’s prediction is proven correct.

Returning to the lions, we spend time with the family and young cubs before a lagoon-view coffee break where we are entertained by fish eagles swooping low into the ponds and returning into the trees with frogs in their talons. As Robert and I enjoy coffee and cookies, I ask him why he chose to work in the Lower Zambezi. He started his guiding career here in 1996 for SafPar, the original owners of Old Mondoro where I am headed next, and then trained with Sobek Travel as a canoe guide. He continued to another company as the only black guide for four years before joining Wilderness Safaris where he was a head guide for 12 years in Kafue National Park. He left in 2016 to return to the Lower Zambezi where he says, “The serenity of the mighty Zambezi River still holds my soul. I was passionate to guide in a park which has a great history of exclusive, fine guiding with such a diversity of activities. I have a great passion and respect for this park and respect for my guests who visit Lower Zambezi as this park does not look to have any idea of being commercialized. It has held the decorum over a long test of time, and I am one of its noble ambassadors.” It’s clear that Robert is a natural teacher, and his enthusiasm for sharing and encouraging his guests to hone their wildlife skills has only grown stronger over time.

Old Mondoro

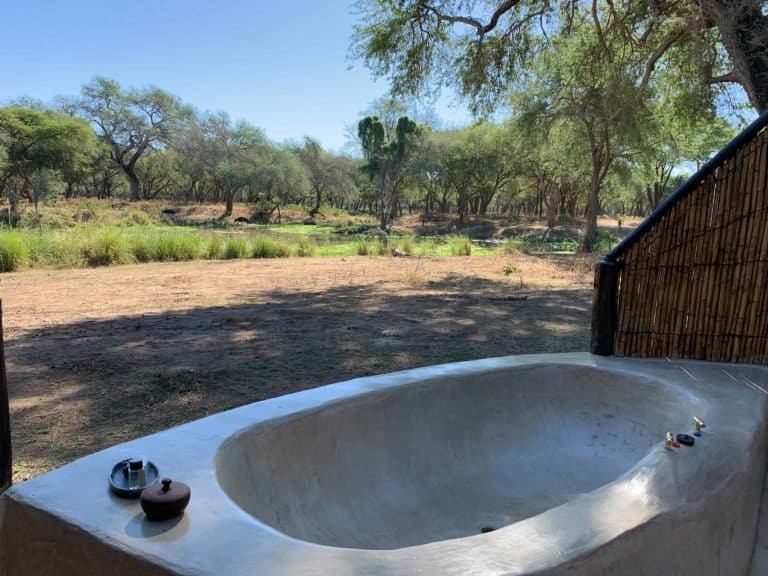

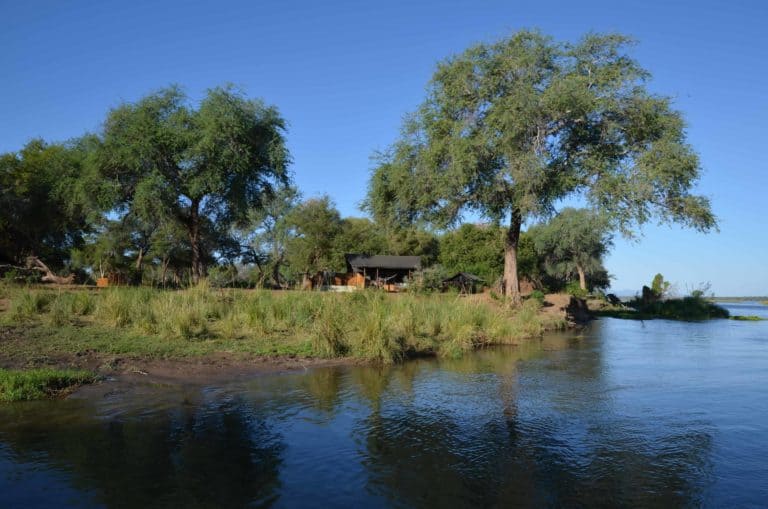

We transfer by road to Old Mondoro, about 30 minutes from Anabezi Camp. This is the most modest of camps inside the national park with five quaint, simple tents spread out from the Zambezi river into a channel frequented by buffalo, elephant, and waterbuck. Sitting right at the river’s edge, the main lodge is designed to frame the view and provide shelter from the sun without infringing on the visitors’ connection with nature. My room, Tent #2, boasts a dual view of the river and the channel; the manager Madeline’s favorite tent tied with #3. While more rustic, Old Mondoro is very genuine with sandy pathways and floor-level rooms. The thatch walls and concrete flooring transition to an open-air bathroom and invisible fourth wall that frames the river.

In the heat of the day, I listen to the hum of insects while ants make a train through the outdoor bathroom, flushing into the drain as I start the shower. I air dry with my kikoi and watch three cape buffalo grazing in the channel. Unlike the other lodges, Old Mondoro purposefully doesn’t offer Wi-Fi in keeping with its more down-to-earth ambiance. The management couple, Mark and Madeline, bring with them several years of managing Singita Grumeti, and their luxury experience blends beautifully with the camp’s casual atmosphere, focusing their attention on special touches to soften its rustic edges. I share camp with two other guests, one of whom is strictly vegan, and am grateful to have the opportunity to see how the staff accommodates. We all enjoy vegan desserts and soups that nobody would have expected were supplemental recipes, and I find myself envious of his grilled aubergine with balsamic reduction.

In the afternoon, after a tranquil boat ride, I share an evening game drive with the other guests, our guide, James, as well as a designated spotter. With no vehicle canopies at Old Mondoro, it’s more important to protect from sun and drink water when traveling in the hot months but offers unobstructed birding. For guests who need the canopy, they can accommodate on request. As the sun sets, the guides transform the vehicle in preparation for the night drive with red headlights and a permanently red spotlight, part of the camp’s leading efforts in environmental sensitivity. We encounter two honey badger, and later a young male leopard casually relaxing in a dry wash. We are distracted, however, by an ant lion that has metamorphosed into its adult form. Attracted by the light, it lands on James’ arm, allowing us a close-up view of this dragonfly-like creature, a far cry from the predatory grub we find within the sand traps. We depart from the leopard and make our way back towards the camp where we see elephants climbing a hillside, hear hyena calling, spot a hippo with a tiny baby, genet, and white-tailed mongoose.

In the morning, we meet for a bonfire breakfast at the river’s edge before heading out on a walking safari. After parking, we don’t make it more than 20 yards before stopping to inspect coral reef-like tubes that encase sticks and grasses, the craftsmanship of termites. The tubes are designed to protect the termites from UV sunlight as they break down the vegetation and return to the mound by underground channels where the fiber creates fungus, which is their food source. The termites are a critical component to the ecosystem, contributing to forest decomposition and preventing natural fires from burning too hot in addition to serving as an important food source for the Matabele ants, birds, and omnivores.

We proceed into the western side of the Chakwenga Plains, stopping to inspect elephant tracks and learn how to size the elephant based on the circumference of its footprint. We find a milkweed plant nearby, discarded by the elephant. James explains that it is poisonous so animals leave it alone, however the African monarch butterfly lays its eggs on the plant, and when the larvae hatch they consume the leaves, which provides the butterfly with the same toxicity as the plant and protects it from predators; its aposematic wing pattern a polite warning to other animals of its toxicity.

Walking through the Chakwenga Plains, we can see where there used to be villages in the park until the 50’s when there was an outbreak of sleeping sickness that resulted in the government moving the villages. Devoid of trees, the plains are stifling on the hot day. We stop to observe a patch of disturbed soil where harvester termites (non-fungus eaters) are busy building their expansive underground network. We continue into the shade of the juvenile mopane forest where we find a pile of what appears to be several different types of animal scat, some with millipedes, some with seeds, and other parts typical canine scat. When James asks what animal the scat belongs to, my immediate response is, “animal, singular?” James explains that the midden belongs to the omnivorous civet with a hugely varied diet, hence the variety of scat.

Back in the forest, James hoists up a skull with the end of his walking stick. It resembles a small human except for the elongated mouth. It is that of a juvenile baboon whose puncture marks on the back side of the skull are proof of its end to a pack of wild dogs.

James amusingly pretends to be lost, but we are back at the car right on time to enjoy coffee and cookies and return to camp for lunch. I take another cold shower, allowing my wet hair to cool me down on the unusually hot day for May, and we prepare for our transfer to Chiawa, the sister camp of Old Mondoro.

Chiawa Camp

We depart by boat from Old Mondoro for a 1-hour cruise upstream to Chiawa Camp. We are greeted on arrival by staff who stand on the dock with cool towels and refreshing welcome drinks and escort us to the main lounge comprising of multiple “rooms” to relax and socialize decorated with locally-crafted sculptures perched in built-in nooks and a large dining room for group meals. With the tall thatch roofing and an open-plan design, the space collectively creates a balance of luxury and—in keeping with Old Mondoro’s style—an immersion in nature.

Unlike the other camps, I am required to radio for an escort in the daytime as well as night due to the potential for wildlife activity. The rooms are tucked in a shaded canopy of old growth forest, all with river views. The room décor is a blend of traditional colonial and beach house with a spacious open plan canvas tent, expansive veranda, claw foot bathtub and whitewashed shiplap divider walls.

At tea, I socialize with other guests who are eagerly sharing their previous day’s sighting of a female leopard being harassed by a troop of baboons, which was broken up when a male leopard showed up to help even the fight. The seven of us at camp are divided into different vehicles, pairing me with my two new friends from Old Mondoro. Chiawa and Old Mondoro both move guests to be with different guides during their stay, unless guests specifically request a guide, and try to provide one private drive complimentary per stay. Our guide is Chris, and he is paired with Abraham as his tracker. Ten minutes from camp, Chris hears a bird call that he doesn’t recognize. We wait to find the source, and he excitedly explains that we have spotted a Retz’s helmet shrike, a common bird to the Lower Zambezi making an uncommon sound. He infers that the shrike is separated from its flock and is using an unusual call to relocate them. Unusual sightings become the trend for this day with three small impala lambs, born outside the typical November season, casually grazing with their alert mothers (being the few lambs available makes their chances for survival to adulthood much more challenging). We continue into the plains overlooking Mt. Chilapira, the tallest point in the range. Here, giant baobabs mix with palm trees among towering mahogany and winter thorn acacias. The scenery is breathtaking. We continue to a “dambo,” or pond, where we sit for sundowners enjoying the family drama of the baboon troop and assortment of wildlife including a single pink-backed pelican, yellow-billed storks, African spoonbill, spur-winged geese, water thick-knees, and crowned lapwings.

As the sun sets, we turn on the red lights and head out to explore a different dambo where we smell a large animal decomposing in the thicket along the shoreline. Nearby, we spot a male and female lion relaxing with full bellies. We continue exploring and encounter two porcupines traveling together as well as a very rare sighting of bush pigs and a single hyena near a decomposing elephant, unable to access the carcass because of the elephant herd on guard nearby.

Back at camp, we enjoy drinks and snacks followed by a “dinner bell” serenade by the camp staff of two gospel songs. For dinner, I select the roasted red pepper soup, courgette pasta with alfredo sauce and a berry custard.

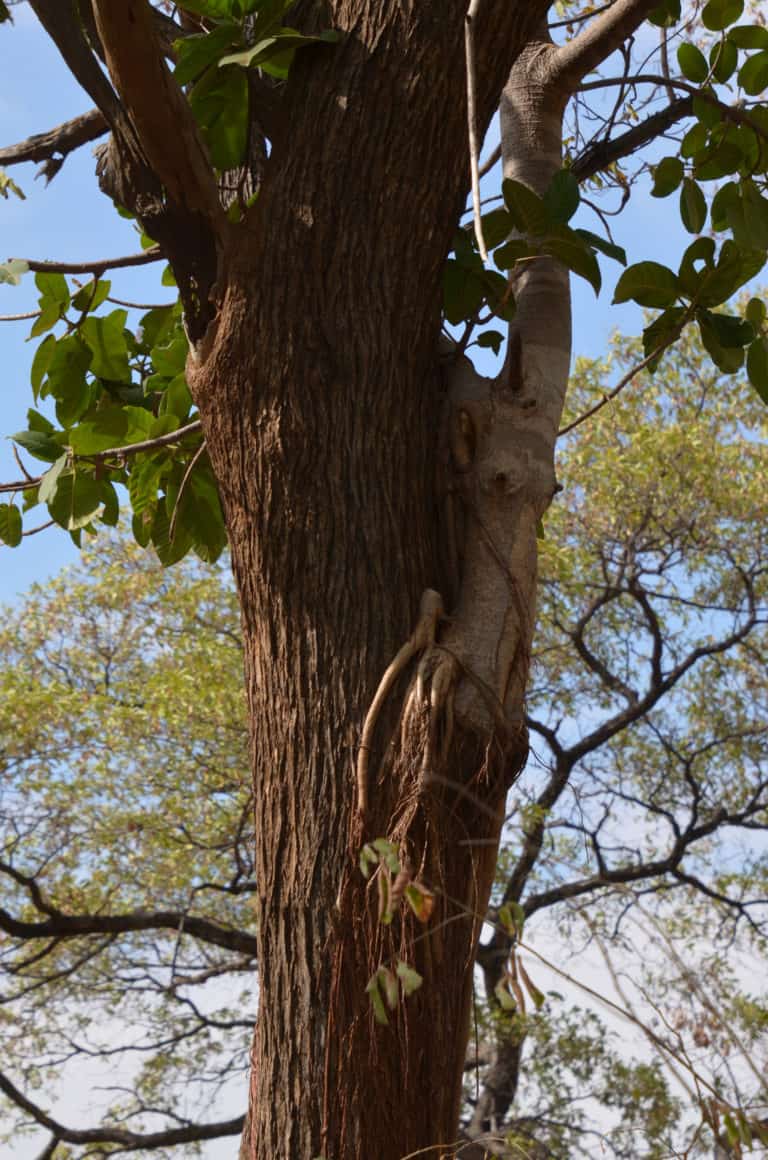

After a morning wakeup of French pressed coffee, we enjoy an alfresco breakfast alongside the river complete with campfire and directors’ chairs. I join a couple from Virginia on game drive who have an affinity for baobab trees. Chris teaches us about the epiphyte figs versus parasitic strangler figs, admiring where the ebony and ivory trunks of a Sycamore Fig and Winter thorn Acacia fuse together with branches entwined. We note the braided trunks of a single baobab and search the dambo for the lions while stopping to enjoy a delightfully sweet cluster of white-faced whistling ducks. We find scaley marks in the sand where crocodiles have dragged portions of the carcass back into a watery grave.

After a stop for coffee, we continue our search for the lions, and to our surprise, the same male and female from the previous night are now accompanied by two tiny cubs. After spending time in the shade nursing her cubs, the mother approaches the water’s edge. The vulnerable cubs follow carefully, hissing as they walk. After quenching her thirst, she moves into the sunlight and passes us as she continues into the dense bushes to hide her young ones. Like many of my cat sightings so far, we have this all to ourselves.

Back at camp, a special surprise awaits us. A floating lunch is prepared with steak and vegetable kebabs, roasted potatoes, fruit salad, and Greek salad complimented by celebratory mimosas. We set off upstream of camp in the Zambezi River, dining and taking in the scenery. A family of elephants has come to the water’s edge to quench their thirst in the heat of the day. Two tiny calves, no more than a few months old, roll and play in the sand. To our delight, one calf, twirls its trunk like a helicopter, sending us into fits of laughter and delivering a perfectly joyful ending to our stay at Chiawa.

Sausage Tree Camp

I depart by boat, heading back downstream about ten minutes to Sausage Tree Camp. I am greeted on arrival by Ruth, the manager, and my private butler, Benson, who is holding a 2-foot diameter white bowl that holds my single fresh towel. With a delicious welcome drink in hand, Ruth and I chat in the main lounge as we overlook what is arguably the most stunning view of the Lower Zambezi of all the lodges in the park as the river bends to frame the tallest peak in the distance. I am escorted through a sandy walkway beneath a canopy of old growth trees to my newly remodeled, open plan, luxury tented suite. The midcentury modern décor of square leather chairs and wood slab counter and a writing desk that float on minimalist iron legs creates a masculine sophistication and modern take on luxury design that allow the view and space to speak for itself. The suite features an entry lounge made almost entirely of mesh screen windows, an open bedroom, sitting area, expansive bathroom, and full floor-to-ceiling sliding screens that open onto a private infinity pool and shaded veranda overlooking the Zambezi River. It feels a world away, where privacy and freedom reign supreme.

After some time to relax, I meet my guide, Patrick and a guide in training named, Prof. Patrick is an examiner for the guiding school and self-proclaimed adversary of anecdotal guiding. He loves to teach and is obliged by my request to learn and be involved in the process when he asks for my interests. We set out, returning to similar areas that I had explored at Chiawa. Patrick wastes no time and quizzes me when we locate a raptor perched in a nearby tree. I identify a brown snake eagle, and he elaborates that it isn’t a true eagle because it lacks feathers on the legs, an evolutionary advantage as the scaled armor protects the bird from snake bites. Patrick points out the sound of small birds alarming in a nearby tree—a sound I hadn’t singled out yet as an important noise against the cacophony of nature. He finds a pearl spotted owlet, the size of a dove, seeking shelter from the angry songbirds in the bows of a dense bush.

We continue through a towering, dark mahogany forest into a dry wash where we find a herd of about 30 cape buffalo then continue into a clearing where Prof notices a green spotted bush snake slithering through the fresh, equally green grass. We stop to observe a herd of impala joyfully leaping across a small stream, a flock of waddled starlings pecking for seeds, and a handsome waterbuck family posing for my camera. Back in the forest, we spot a Verreaux’s (Giant) Eagle Owl and an old Duggar boy Cape Buffalo who we woke from an afternoon siesta.

We return to the plains below the escarpment where we enjoy sundowners as the Marabu storks cluster in a baobab. On our way back, we encounter a bushy-tailed mongoose, and then I enjoy drinks around the fire at the lodge with Ruth and Allan, one of the two directors of Sausage Tree who is in town for Conservation Lower Zambezi’s 25th-anniversary celebration the next day. We enjoy rosemary-buttered popcorn as we discuss the great achievements they have made over the last decades, the perils that threaten their work, and the direction forward for Zambia’s conservation tourism efforts. With the daily tourism fee contributing to the funds, they have succeeded in growing their wildlife protection efforts—often converting poachers into rangers—, developed environmental education and community support, reintroduced wildlife, and implemented ongoing research projects.

After falling asleep to a chorus of frogs, I awaken to the cheerful chatter of whistling ducks and water thick knees. As the sun rises, I enjoy a veggie omelet, fresh fruit, and coffee along the breakfast bar that overlooks the Zambezi River before setting out on a walking safari. Patrick drives us to the dambo at Twin Baobabs, where the male and female lion with tiny cubs has been frequenting. We spot fresh lion tracks and park the vehicle to begin our walk north, away from the dambo. We climb a short hill into the thicket so as not to startle the marabou storks that are busy stalking catfish in a nearby pond. We skirt a termite mount and sit on the hillside overlooking the pond. An African fish eagle swoops down and scores a catfish so large that it can only manage to fly a few meters above the ground and disappears into the forest. One of the storks hoists a giant catfish from the water, and with a similar issue, is sorting out how to swallow it whole. A few storks watch with jealousy while others are busy feeling around for catfish in the murky water, their beaks a tool to measure the sizes of the fish to determine whether they are small enough to eat. After a few minutes of deliberation, the stork lifts the catfish and manages, with some effort, to swallow it whole.

We continue from the hillside heading away from the dambo, stopping for a banded mongoose and various tracks. Patrick discusses the history of the Amazon frog beat, an invasive plant that is often confused for water hyacinth, another invasive plant that was introduced from a private fishpond in Egypt in 1847. Both spread exponentially, but frog beat is doing even better than hyacinth as its leaves saw through the neighboring plants as they rub together from wind and waves. We see hippos fighting, emerging mouth-to-mouth from beneath the floating greenery of the frog beat. We stop to watch the Cape turtle dove drinking, sucking in water from its beak, unlike other birds that scoop water with their beaks that drips into their mouths. We are accompanied by groups of banded ground ring dragonflies as we cruise through the sand, stopping to identify the porcupine tracks with the notable quill drag marks and the “hippo highway,” a path forged as two separate treads from heavy, lumbering feet that never cross. Suddenly, white-backed vultures arrive from all directions. Excitedly, Patrick notices three vultures in the forest across from us sitting on a termite mound, but the rest are choosing not to land. He predicts that it was either a false alarm or not a big enough meal to justify joining the party. So, we continue our path, eventually returning to the vehicle after 3 hours. We enjoy a coffee break then set out on a game drive to see if we can find what was attracting the vultures. Patrick pulls up to the termite mound, startling a brown snake eagle that flies off and leaves behind an opened catfish—the very catfish that was abandoned by the African fish eagle when it became too heavy to lift. Nothing goes to waste, though, as other birds of prey take over. From here, we continue around the dambo where we spot a female lioness sleeping across the pond as well as the male lion in such a peaceful slumber that his ears don’t even perk up as our vehicle approaches through the grass.

We return to camp where I have time for a brisk dip in my private plunge pool and a rest before we meet up for a special lunch. We set out by boat across the channel to a sandbar where we exit the boat barefoot into ankle-deep water. Beneath the shade of white canopies, we enjoy fresh salads, kebabs, and pesto encrusted fish fillets as the Zambezi river flows around our bare feet. Dessert is a melon and strawberry custard with a pair of African fish eagles in their nest and a grazing elephant as the backdrop.

Back on shore, I get ready for my afternoon canoe. We set out by boat to the start of the canoe trip, about twenty minutes downstream, past Chiawa, to the Chifungulu Channel. A second canoe and guide accompanies us as it’s safety protocol to have at least two canoes on every trip. We enter the channel, keeping to the shallow waters where we can avoid antagonizing any hippos. I help paddle, but Patrick is happy to steer and paddle when I want to snap some pictures. The views in the channel and chances to see wildlife are much better than in the main Zambezi river where the embankments are steeper. In the channel, we are at eye level with the chattering water thick knees, floating jacanas, timid hippos, and grazing herbivores near the riverbanks. Cape buffalo stare us down, as still as giant boulders except for the flicking of their droopy ears. Hippos peek out of the water, keeping a close watch as we drift into riverbends and sink into the deep dark water for safety. Crocodiles sun themselves on the sandbanks and skirt into the dark river, their floating debris of water plants the only indication of their presence. Occasionally, Patrick taps his paddle against the canoe to politely warn hippos of our approach, my heart beating faster as they crowd into deeper water, their wakes rocking our canoe as they relocate.

As we cruise peacefully to the sounds of the lapping paddles and the birds, a goliath heron stands statuesque in the center of the river when suddenly an African fish eagle dives from the tree and bombs the poor heron, which lets out an angry squawk before flying further downstream only to be attacked again by the fish eagle. The heron continues flying downstream and the eagle attacks a third time before finally leaving it alone. Perhaps the eagle saw it as a threat to a nearby nest as the largest of the herons would certainly enjoy an egg or eagle chick meal. The channel attracts all sorts of water-favoring birds including grey and goliath herons, saddle-billed storks, open-billed storks, cattle egrets, ibises, crowned and blacksmith lapwings, water thick knees, bee eaters, kingfishers, and songbirds.

The canoe trips are always done in the afternoons, in part because the lighting is better, but also because of the higher chances of wildlife coming to the river to quench their thirst. This is the case today as well, and we glide our canoes to the island shore across the channel to sit with a breeding herd of elephants. We watch, quietly as they huddle together at the water’s edge, sucking in gallons with their trunks and shooting the water like a firehose into their mouths. A tiny calf, still too young to use its trunk, leans down on its front legs to drink right from the river. The sandy bank is steep with a three-foot cornice at the top, and we watch as the young mother patiently aids her calf in the journey back up the hill, returning a few times to the bottom when her calf collapses in a playful heap before clumsily hoisting itself back up the hill. Deep grumbles come from the young mother, and one of the adults responds to assist. They allow the calf space to try on its own but are there to help if needed. With a final beached-whale move, the calf hoists its back knees up over the embankment and is free to continue exploring with mother on the plateau.

Further downstream, a lone bull elephant is grazing on trees on the right bank, scratching his face in the branches as we approach. His casual demeanor changes like the flip of a switch as we turn the bend. Unbeknownst to us, he intends to cross the river and our presence is not an acceptable delay. Suddenly, he charges our canoe, ears wide and splashing through the water. Patrick raises his paddle and slaps the water with a large cracking sound that surprises the elephant and stops him in his tracks. Our second canoe guide is close by and we push through quickly to give the big bull his space. Shortly after, he begins a cheerful journey through the water to the north bank.

With great satisfaction, we return to the motorboat where we enjoy sundowners and snacks on the way back to the lodge. Following our return, we quickly set out for an abbreviated night drive. Our sightings include three honey badger, a thick-tailed bush baby, and white-tailed mongoose. By the light of the moon, we sit in the dark amongst the deep guttural groans and silvery shadows of an elephant herd.

Chongwe

In the morning, I head to the nearby sister camp, Potato Bush for a quick visit. A similar layout, but different décor and camp style differentiates Potato Bush from Sausage Tree. With family-style dining, the camp is good for a smaller, more social gathering. The rooms are similar in size to Sausage Tree but are designed in a traditional colonial fashion with warm colors and tapestries. Only a short boat trip away from one another, the camps utilize the same areas for game drives, so the wildlife experience is identical.

I set out upstream to the entrance of the Lower Zambezi National Park, approximately 30 minutes by boat. At the confluence of the Chongwe River and the Zambezi River, I am greeted by the Chongwe River Camp staff, and again a cold towel and a fresh drink. I receive a big welcome hug from one of the managers, Nezzy, and my room attendant, Tryfell, takes me along the pathway to my tent, #6. While the rooms are closer together than the other camps, the simplicity of the tent layout is one of my favorites with room to walk on both sides of the bed, a headboard dividing the room, and a large open-air bathroom that sits lower to the ground behind the bedroom for privacy. With proximity to the water’s edge, I have a young bull elephant as a daily afternoon visitor who I watch bully away baboons and warthogs as he browses and cools himself in the shallow water. I enjoy the variety of birdlife from the room including fork-tailed drongos, red-billed hoopoes, white fronted bee eaters, pied kingfishers, tropical bou bous, waxbills, and more.

After a bit of lemon poppyseed cake at tea and the entertainment of two striped skinks in courtship, we set out for our afternoon game drive. Ronald, my guide, is in his mid-twenties, but what he lacks in extensive guiding history he makes up for in intuition and enthusiasm. We stop to admire the enormity of the hammerkop nest, and Ronald explains that the bird typically lays three eggs, one of which is a decoy. We pass a waterhole used in dry months with a hide that can be a post-dinner “night drive” for guests keen to see nocturnal species. With the number of aardvark dens in the area, it could offer good chances to see these unusual creatures. We find kudu, bushbuck, elephants, hippos, and hoopoe birds on the way to the park gate, which takes us about ten minutes to reach. Ronald explains that in recent months, they have located two transient wild dogs that appear to be pregnant and the male lions from the Chiawa region reign over the western territory with a lioness and cubs somewhere in the area. We stop to admire Cathedral Baobab, aptly named as scientists have dated this magnificent tree to be over 3,000 years old. We find a very relaxed elephant herd with a tiny calf that allows us to remain quietly close by as they casually snack on cumbratum bushes.

We enjoy sundowners in the Inkharange Plains where I enjoy a Malawi Chandy (ginger ale, soda water, and bitters) and snack on mini calzones, hummus, and veggies. The night drive is quiet as the moon grows fuller by the day. We encounter a few scrub hare, bushy-tailed mongoose, and a large spotted genet.

In the morning, the campfire is ready for a breakfast of fresh fruit, porridge, and a cooked egg to order. We depart for the game management area to explore a new region on foot, sandwiched between the foothills of the mountains and the Chongwe River confluence. It is drier, save for the waterhole built by the Royal Zambezi Lodge where a few antelope are lingering including the only zebra I have seen since the first day on safari as they tend to prefer the mountain regions until dry season brings them to the riverfront. We walk down a sandy road with tracks of a lioness that crossed in the night. We continue into a dry riverbed pocked with aardvark holes. We find civet tracks, the web of a funnel web spider, the nests of white-browed sparrow weavers, impala, squirrels, francolins, and a colony of dwarf mongoose. After returning to the vehicle, we drive up the hillside to check out the fly camp site, which offers an impressive view into the valley and the Zambezi River. We return to camp for brunch and a siesta.

Since our last two activities were relatively quiet for wildlife, Ronald makes a plan to venture deeper into the park, and we set off after tea. Twenty minutes later, we are crossing the Chiawa dry riverbed, and after fifteen more minutes, we encounter another guide from Chongwe, Hugo, with his guests who requested a full day trip in the park. I am also reunited with my guide from Chiawa, Chris, who is sitting with his guests near a dense bush that houses a yearling leopard on a fresh impala kill, her mother close by relaxing in the grass. As the adult female stretches and moves into dense cover across the road, Ronald chooses to drive farther down and stops to wait. His instincts were right, and the leopard returns into view, stopping to relieve herself before crossing again into the thick underbrush. We follow for a bit as she uses the dense vegetation for cover, likely making her way to the waterhole to quench her thirst. We skip sundowners in exchange for the company of the yearling leopard who is casually relaxing in the grass. As the sun departs, we get out the searchlight and continue our drive, running into a honey badger not ten minutes later. En route west, we stop for a hunting civet and spot two white-tailed mongoose, impala locking horns, and two thick-tailed bushbabies before returning to camp for my final night in the Lower Zambezi.

Lower Zambezi Summary

After a full week in the Lower Zambezi, I had amazing meals, service, and guiding quality throughout. So, the major differences between camps are locational strengths and camp style. Among those, the Chiawa / Sausage Tree location was by far the best balance of incredible scenery and wildlife viewing, however the Old Mondoro / Anabezi region was by far the most productive area for cats with 14 leopard sightings in three days, 13 of which were from Anabezi alone. Chongwe is a great spot to kick back and enjoy birding right from camp or have access to fly camping and cultural experiences from the nearby villages, but they are a 30-minute drive to reach the Chiawa riverbed which they rely on for the most reliable wildlife sightings. With so much to explore and so much activity variety, my recommendation is to utilize one of the Stay 4 nights / Pay 3 nights specials or a 7-night combination between Chiawa/Sausage and Old Mondoro/Anabezi, if time allows. This year, Zambia is suffering from the worst drought since the inception of Conservation Lower Zambezi 25 years ago, inevitably applying greater pressure on the protected wilderness areas as well as the country’s third pillar of its economy, agriculture. The Lower Zambezi is typically verdant with abundant water holes in May, however this year it is posing more as August conditions with predominantly dry, short grasses. For mammals, this park is best close to peak season, but shoulder season delivered well this year as drought plagued the summer months. If iconic species, such as giraffe are expected, then the park is best blended with other regions in Zambia, Botswana, or South Africa to provide the variety. To learn more, see our sample itineraries.

Victoria Falls

Tongabezi Lodge

After a quick campfire breakfast, I am transferred to the nearby Royal Airstrip to board my flight to Livingstone via Lusaka. By mid-morning, I am greeted on arrival in Livingstone and transferred to Tongabezi Lodge located about a half hour upstream from the Zambia side of the mighty Victoria Falls. On arrival, I am escorted with a refreshing welcome drink and cold towel through a chic lobby featuring large, hand-carved wooden doors to the curio shop and serves as the gateway into lush gardens that spread down the hill towards the Zambezi River, weaving public spaces and various rooms into a relaxing retreat where guests can find their own nook to escape and unwind. The guest lounge resembles a bohemian beach house living room that opens to the Zambezi River. My cottage sits nestled above the river with an expansive private deck shaded by mature trees. The cottage entry nook, with small, arched wooden doors, reveals a corridor of blue-black tile, transporting me into a large, bright, rondavel bedroom. Curving around the room, the entrance to the bathroom opens to a claw-foot tub framed by a large picture window and shower of black and white starburst tile.

The lodge offers a variety of activities, however with just one afternoon and having been to Livingstone several times, I opt to relax. After a delicious lunch on the deck of fresh beet salad, carrots, potato fritters, and steak, I am taken on a tour of the Tongabezi houses, each a unique and stunning design. We pass through Nut House, a Greek-inspired suite of white concrete and bright furnishings, Bird House, and my favorite, Tree House, which encompasses its own private corner overlooking a lofty view of the Zambezi. The house envelops a living tree with mahogany floors, an open plan bathroom, changing area, lounge, and bedroom for a luxurious immersion in nature.

Liuwa Plains National Park

KING LEWANIKA CAMP

Liuwa Plains National Park sits in the remote western corner of Zambia. A unique display of ecosystem duality, the park transforms from shallow wetland into a Serengeti-esque ocean of grass that provides habitat for a unique cross-section of species. Mainly a remote and challenging park for self-drivers due to the deep Kalahari sand, the park has been open to the serviced safari market for only three years with the inception of King Lewanika, and it remains relatively unknown to the safari world.

Departing from the Livingstone Airport to Liuwa Plains, I am the only passenger in the entire airport at 6:30 in the morning. I am greeted by the pilot, Dusty, as I cross into the airport threshold and escorted by a Proflight representative to the awaiting Cessna.

After an hour, we touch down at the Kalabo Airstrip—pot-holed and partially overtaken by grasses. We are surrounded by a cross-section of Liuwa Plain’s history and future with rural fields, one airport hangar where a team from African Parks is conducting a scout training, an office for the local weather meteorologist, and battered buildings occupied by the construction company in charge of paving the road to Angola. I am greeted by Gloria and Isaac from Time + Tide who offer me coffee and cookies while we wait for the helicopter. The departing guests arrive, and we are greeted by the helicopter pilot, David, who exchanges passengers with Dusty. We lift off like a dragonfly, above the paved road where we see a few children and people on bicycles, passing farmland, and quickly soaring over endless grassland. We spot crowned cranes, and David gives us a close-up view of zebra, wildebeest, and circles back to a waterhole with the largest buffalo herd he’s seen since arriving three months prior. We pass over vast grassland and touch down on an island of trees where the team from King Lewanika is waiting to greet us.

From King Lewanika, it is abundantly clear why the company’s name of Time + Tide is so appropriate. Here, as the only serviced camp inside the national park, visitors have all the time to explore at their desired pace. The seasonal nuances, or tides, transform the Liuwa landscape from an Okavango-like oasis of red lechwe with hundreds of birds and water as far as the eye can see into a predator-rich Serengeti-like grassland where wildebeest bulls stake their territories and cheetah disappear into the golden plains. Typically, this time of year, there should be a vast wetland where wildebeest and their calves would be grazing in the plains until June, but because of the drought they have already begun their return journey north towards permanent water. To adjust to the conditions, my time in Liuwa Plains focuses heavily on game drives to locate the resident predator species with the help of tracking data from the Zambia Carnivore Project rather than walking, swimming, and boating.

We are escorted through the forest on pathways of packed Kalahari sand where the unassuming front entrance of King Liwanika opens to expansive grasslands. Gloria explains that the architect’s concept for the lodge was inspired by dragonflies. The pathway from the helicopter curves gracefully through the trees to resemble a tail. The main lounge, with its geometric I-beams braced at 30- and 45-degree angles and connected by grass thatch, is the boxy head of the dragonfly, and the wings are the large, private suites spread out in both directions along the edge of the island.

My open-plan suite is a modern take on canvas tented design with a full wall of floor-to-ceiling mesh windows overlooking the grasslands. The grey, cognac, and beige motif with simple black-trimmed furniture takes an elegant approach to mid century modern design that, warmed by the colors, blends with the natural surroundings, complemented by the bold horizon line of the grasslands. The only sound is the chatter of vervet monkeys and the cooling breeze as it passes from the grassland into the room.

After tea, we set out for the evening drive. The Kalahari sand is so deep that the vehicles must remain perpetually in four-wheel drive, so we cruise casually through the sand and tall grass. Robbie takes us to a grove of trees where he shares the legend of Lady Liuwa, the only lion left in Liuwa after the extirpation of lions by poachers during the civil war in Angola. Auspiciously, she was first discovered beneath the grove of trees where we sit, which was the burial ground for the region’s king and his family. As such, the locals believed her to be the reincarnation of the daughter of their deceased King Lewanika and have celebrated the return of lions to Liuwa to continue their king’s tradition of protecting wildlife. Lady Liuwa passed away a few years ago at an old age but served as the matriarch to a small family of lions who she adopted after they were introduced from Kafue National Park and have passed on their lineage to next generations. We continue to another grove of trees where we discover two young male lions, the offspring of one of the females who was introduced from Kafue National Park named Sepo, meaning “Hope,” who recently died protecting her cubs from a male that had been brought in from Kafue in 2017. We watch the two brothers as they relax in the grass, unaware of their precarious circumstance as two of only ten lions in the entire national park. As the sun sets, the moon is also rising, and we take in what Robbie coins as “ABWAS”, Another Bloody Wonderful African Sunset.

In the morning, I step out of my room with a short walk to the main lounge, keeping an eye out for any visitors. I am unaware that a female cheetah and three cubs were spotted this morning near the staff quarters. I make my way to the campfire where I am poured a fresh cup of coffee, and before Robbie can even make it to his seat, he points behind me, where the island of trees meets the grass on the other side of my tent. “Cheetah!” he whispers excitedly and instructs us to take a seat and remain still as the cheetah leads her cubs away from the lodge and across the field. We continue enjoying our breakfast while Robbie radios the Zambia Carnivore Programme to notify them of the sighting. Shortly after, a motorbike appears and drives off into the field to trail the cats. We follow soon after, keeping a distance as the cheetahs continue in search of food.

With no food options nearby, we decide to investigate a report of hyenas on a kill and plan to return to the cheetahs later. We pull up to three hyenas on a fresh wildebeest kill while a crowd of white-backed and lappet-faced vultures wait their turn for scraps. Nervously, two hyenas work on the carcass with regular breaks to look up, skittishly, as the third hyena keeps watch for competition. They know there are lions nearby. We find another group of three polishing off some bones as the matriarch works on the open skull of a wildebeest. We then return to the cheetahs where we sit and chat with Peter, the researcher for ZCP. He explains that the cheetah is #180 and has three female cubs around a year old. They have identified 15 individuals from fecal samples; however, they have seen more than 20 including three new males. They plan to collar one of the three female cubs once she has stopped growing and have three other cheetahs currently collared. They have also begun collaring the wildebeest to keep track of the herds’ movements and record the interaction with predators as they migrate seasonally.

We watch as the cheetah cubs casually follow mother through the tallgrass. Sadly, as they progress toward an oribi in the distance, one of the cubs accidentally flushes out an animal, taking off at a full sprint until she discovers she is chasing a jackal. Their cover is officially blown with every wildebeest nearby glaring scornfully. They will have to wait patiently until their neighbors forget they are there. We stop for a coffee break on a shaded island of strangler figs and make our way back to camp.

In the evening, we set out with the most recent coordinates from ZCP to relocate the cheetahs, stopping to admire a juvenile saddle-billed stork. A red-necked francolin with a tiny chick scurries through the grasses as the vehicle kicks up fresh scent of sage from the milsonia grasses. By the time we reach the coordinates, however, the cheetahs are nowhere to be found. They have disappeared into the ocean of grass, so we set off to find the lions that, according to ZCP, had stolen the hyena’s wildebeest earlier that day.

The sun hangs low as we approach a grove where we first make out the face of a lioness relaxing in the grass. One face becomes two, then three, and the adolescent female relocates closer to our vehicle, locking eyes with Robbie, then me as she yawns and considers whether we are edible. The anecdotal adage that lions don’t see people in the car is clearly false when faced with a lion making intense eye contact. We sit statue-still while the playful cub stalks its cousin, who in turn, is stalking us. As the cub approaches, her big cousin turns to notice so she pounces playfully. The adolescent female stands up and begins walking toward our vehicle, so Robbie repositions us farther from her, explaining that she has a reputation for puncturing tires. As we move, the cubs slowly stalk the vehicle, and I feel an intrinsic terror at being momentarily, albeit not seriously, targeted by these killers-in-training. Our movement startles the dominant male, and he lifts his head to reveal a beautiful, full, dark mane. He is the son of Sepo—one of the cubs she died protecting. He is also the father of the two males we saw the day prior who are also Sepo’s; a consequence of having too small of a lion population, and one that African Parks and Zambia Carnivore Programme hope to remedy with further, careful reintroductions to reduce the chance of inbreeding without harming the existing population. We missed the sunset but still stop for cocktails, awestruck by the clarity of the full moon. Returning to camp for the evening, we dine on croquettes, basil alfredo linguini, and an apple crumble for dessert.

Today is coldest morning so far, and winter seems to have arrived within the last few days. Robbie plans to take us a new direction farther south about an hour’s drive from the camp to a known hyena den. As we set off, he picks up the radio to collect any updates from ZCP, remembering in typical friendly Zambian fashion to start with polite small talk, asking each other how they are doing this morning and when they might be able to see each other again. We note that the lions passed through camp during the night, stop to observe a white crested helmet shrike and a herd of frisky Zambiensi zebra, a subspecies of Burchell’s, cavorting across the road.

We find a martial eagle on the ground and a side striped jackal before we arrive to the den. Here, we discover two females and eight young cubs. While the females calmly sleep, the cubs hide in the den, a few popping out occasionally to inspect the visitors. There are over 50 members of this den and 7 known active dens in the park. As we return, we stop for a coffee break near a pan where a few bachelor wildebeest are grazing and one cruises through the knee-high water, passing a Temmick’s courser, dozens of crowned cranes, and white pelicans. Further down, we spot a rock monitor lizard. In the only palm tree in the entire park, which legend claims rooted out of the walking stick of King Lewanika, we spot a pair of nesting red-necked falcons.

In the afternoon, we set out for the west in search of the migration herds who have been found in the area, likely attracted to the smoke from agricultural slash and burn fires to combat the poor growing season. We work on our birds as we drive, noting a swallow-tailed bee eater and a hoopoe as we depart from camp. Robbie also identifies a tchagra, black-eyed bou bou, yellow-throated petronia, and southern puffback along the way. At a nearby water pan, we find dozens of waddled cranes intermingling with the relatively dwarfed crowned cranes and watch with amusement as a plucky crowned crane faces off against a towering waddled crane for some unknown offense.

Among them, we spot a pied avocet, red-winged prattingcole, black-winged prattingcole, black-winged stilt, green shanky, and western yellow wagtail along the shoreline. We finally arrive to the wildebeest herds where nearly weened calves still convince their mothers to suckle as they cruise through the golden fields in search of access to best water and grazing. We observe the herds as the sun starts to set, then cruise through the tall fields of grass to reach an island where the team has arranged a special sundowner spot.

Our barman, Terry, is awaiting with warm towels for us to freshen up and presents a bottle of Veuve Cliquot. “Would you like me to make the popping sound?” he asks with a bright smile, and I respond with the only correct answer, “Yes, please!” We celebrate my final night in Liuwa Plains with champagne, popcorn, and biltong before returning to camp for a traditional Zambian gourmet meal.

Summary

Liuwa Plains is a destination that can only be truly known by experiencing it in its various seasons, but April through June is a nice blend that typically allows you to catch the migration of wildebeest as well as the birds and waterways. In April, you may catch the local Losi tribe’s Kuomboka festival when their king moves from his summer home in Lealui to Limulunga. The bird life as well as the carnivore opportunities are well worth the journey for those intrepid travelers who want ultimate exclusivity, flexibility, and unpretentious luxury.

My husband lived in Zambia during graduate school, and during his time in the Eastern Province in the town of Chipata, he began a regimen of jogging daily. This peculiar behavior attracted many onlookers, curious about the new “muzungu,” or white person. On one occasion, a young girl joined him, riding her bicycle alongside, speeding up to race him with a smile but no words exchanged. On a different day, a man joined him, proudly pumping his fist in the air shouting, “JOGGING!” or “EXERCISE!” as they passed amused onlookers. When I tell this story to the Zambians I meet, they always laugh with a knowing satisfaction. Yes, that is what a Zambian would do. It is a country of over 70 tribal languages plus Nyanja, the business-transaction language detached from any tribe, and a history of peaceful coexistence. It is a country of people with a sense of humor; naming their largest mountain in the Lower Zambezi National Park, Chilapira, meaning, “I shall never again,” and the word for scorpion translates to, “cry all day.” There is a joyfulness to people here; a friendliness that has welcomed me on each of my visits over the last ten years. It is a country that currently suffers from a 60% unemployment rate but maintains an infallible spirit. The successes of the tourism industry and the connected conservation efforts reflect this, as they have worked tirelessly for decades with limited budget, a hobbled economy, and a government bloated by inefficient bureaucracy. Despite the challenges, it is a country of genuinely warm, welcoming people who—like their parks—are motivated by an intrinsic energy to do well and a vision for what conservation tourism can achieve.